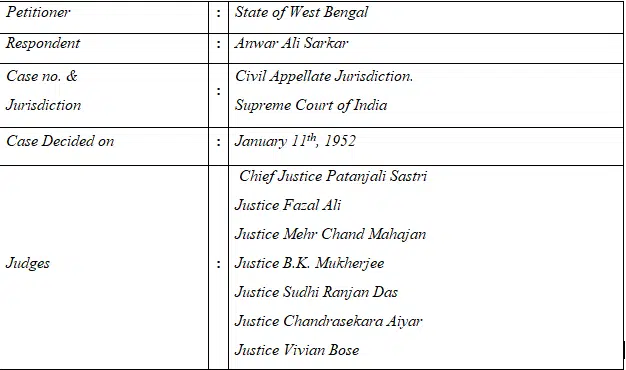

Primary Details of the case:

Case Brief ON STATE of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar (1952) SCR 284

Introduction:

Last and foremost, it is important to know whether any classification has been provided under the Indian Constitution through article 14 or not before considering the case brief? If yes, does it not defeat the very nature of anti-discriminatory law under article 14? Yes, Article 14 allows reasonable classification and is one against class legislation. This principle of reasonable classification was laid down in Y. Srinivasa v. Veeraiah (1993). One of the essentials as per the twin test laid in Veeraiah case was that reasonable classification under article 14 was permitted and should be such as ensured that such classification had reasonable nexus or rationale nexus with objectives sought for while doing such classification. The subsequentcase dealt with this concept of reasonable nexus under article 14 of Indian constitution. The following are facts and issues.

Facts:

The facts of the case were that west Bengal state had made a statute called West Bengal Special Courts act 1950 which aimed at ensuring that there is a quicker trial certain types of offences.Section 3 gave power to the state to form special courts for purposes of this act and section5 authorized state government notification about trial class cases which would be determined by them.Basically, the act prescribed a few procedural provisions relating to trials in special courts resembling those found in code of criminal procedure.The respondent who was earlier petitioner challenged this particular act on basis that it violates/contravenes principle enshrined in Article 14of Indian Constitution.Calcutta High Court ruled in favor of the Petitioner but State Government appealed against it in this present appeal.Following are issues.

Issues:

- Whether Section5(1) under West Bengal Special courts act,1950 violate test laid down under Article 14of Indian Constitutionor not?

Laws involved:

- Article 14 – Right to equality

- Section3of West Bengal (special courts) act,1950 –the power of the state government to establish special courts

- Section4and5–the power to appoint judges to special courts under the act, 1950.

Contentions:

- The learned counsel for respondent argued against enactment of 1950 and stated that object or preamble of act of 1950 should not form basis for classification and there is great amount of powers coupled with unguided limitation on government as per section 5(1)of this Act in making classification thereby allowing state to practice invidious discrimination in very bad manner. Additionally, he pointed that this law discriminates between two wrongdoers who are not meant to be classified so. Thus, according to him, this section violates the objective it was supposed to achieve since there was no rational nexus in placing a stranger at a lower pedestal than servants while such strangers will be produced before special court under laws but nevertheless they shall not come under this act unlike servants.

- However, the petitioner’s counsel relied upon the public interest

- argument and submitted that classification of article 14 is not a concern.

- The law in question must have been enacted to serve public purposes

- and make dispute resolution faster as argued by counsel for the petitioner;

- hence there was no need for classification under article 14. The learned counsel said that any legislation which does not infringe on any individual’s or group’s right but instead caters for general welfare of all is not arbitrary in nature. Therefore, it cannot be deemed as being discriminative and thus violating Article 14.

Decision:

- The decision in this case comes from seven-judge bench where six judges were in majority while one judge gave his dissenting judgment. Out of six, two concurred with the majority. Let us see each reasoning as follows.

- Firstly, Justices – Fazal Ali, Mahajan, Mukherjee, and Aiyar gave identical reasons. They held that article 14 of the Indian Constitution enjoins equality before law; therefore everyone should be treated equally when relief or defence is given without distinction. Accordingly, if an individual alleges that a particular legislature has disabled his fundamental rights through legislation he should not be tried till he has had an opportunity to prove that his rights have been abridged by the law.As such no legislature can say at any stage that the purpose of its enactment was not to discriminate against anyone either singular or plural or preclude operation of article 14 of our constitution.So according to them section 5(1) empowers state government to refer any number of cases to the special court without limitation on it so as not violative of article 14.But then this statute enables discriminatory acts along with administration and hence lacks reasonableness.Therefore void.

- Secondly Justice Das opined that powers under Article 14 are not taken away from states but according to him what is required is only reasonable nexus between classification and object of law. According to him Section 5 does not validate the classification made according to a law as it allows for cases to be classified based on the ever changing moods and fancies of the states, which is discriminatory and therefore void.

- On his part, Justice Bose found that under article 14 the true test is not one of complete classification or absolute equality in fact it would amount to determining whether we are a sovereign democratic republic as mentioned in our preamble. Hence, thesection failed to secure equal treatment under article 14.

- In conclusion, Chief Justice Patanjali Sastri did not agree with the said section to be discriminatory and void. He argued that the impugned act of 1950 did not in any way purport to disable equal protection of laws to any person or any class of persons as claimed by the majority. There was therefore no discrimination motive behind the enactment of the said section by the legislature and therefore it does not contravene Article 14 of Indian Constitution. So he dissented.